Dave Alber’s article “A Brief Introduction to Chinese Temples” appeared in Suzhou, China’s Suzhou Review newspaper on April 9, 2018.

A Brief Introduction to Chinese Temples contains the following travel illustrations by Travel Writer Dave Alber:

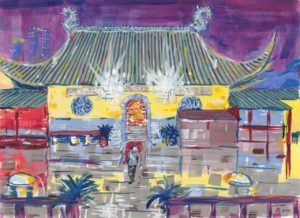

• Approaching Dongwu Temple on Chinese New Years Eve (Suzhou, China)

A PDF file of the published article is here: “A Brief Introduction to Chinese Temples” in Suzhou Review newspaper, April 9, 2018.

The article is reproduced here:

A Brief Introduction to Chinese Temples

by Dave Alber

Last week, I went to Shanghai to meet a friend visiting from the United States. After having lunch together, we walked to the Shanghai City God Temple. Although I’ve become accustomed to Chinese temples, having lived in China for four years, my friend was surprised by the multitude of banners, deity icons, incense offerings, and the rhythmic chanting of the monks. “It’s a bit overwhelming,” he said, taking a seat. “It’s baroque in its complexity, but totally alien to me in its iconography. I can’t make heads or tails of it.” Inspired by my friend’s confusion, I decided to write a brief introduction to Chinese temples.

Last week, I went to Shanghai to meet a friend visiting from the United States. After having lunch together, we walked to the Shanghai City God Temple. Although I’ve become accustomed to Chinese temples, having lived in China for four years, my friend was surprised by the multitude of banners, deity icons, incense offerings, and the rhythmic chanting of the monks. “It’s a bit overwhelming,” he said, taking a seat. “It’s baroque in its complexity, but totally alien to me in its iconography. I can’t make heads or tails of it.” Inspired by my friend’s confusion, I decided to write a brief introduction to Chinese temples.

Chinese temples are commonly of three varieties, Buddhist, Taoist, or for Chinese folk religion. That said, many temple complexes are syncretic, in that, although they predominantly represent one of the above three traditions, they also contain shrines for other traditions. For example, Suzhou’s Dongwu Si Temple is emphatically Buddhist, however it contains a large shrine room of folk icons for folk religious services.

Upon visiting a Chinese temple, how are visitors to distinguish whether a temple is Buddhist, Taoist, or for Chinese folk religion? Start by looking at the names. When looking at the names of the temples, miao refers to a folk temple; guan refers to a Taoist temple or monastery; and si refers to a Chinese Buddhist temple. When examining a temple’s appearance, one finds that Buddhist temples are often (but not always) red and gold, while Taoist temples are often (but not always) more subdued in color with shades of greys. Upon entering the temple, the visitor should notice the people operating the temple. Are they dressed as monks or wearing a pre-modern uniform? Buddhist monks’ robes are often yellow, gold, red, tan, or grey. While Taoist priests wear an outfit that is often grey, blue, and black, but is most identifiable as being a religious uniform from China’s dynastic period.

Buddhism is complex, and Buddhist temples in China are representative of three stages of the religion’s history. In its 2500 year history, Buddhism has gone off in several different directions: the original monastic Buddhism is Theravada; the popular icon-rich polytheistic Buddhism is Hinayana, the uniquely Chinese Taoist-influenced Buddhism is Chan (Zen in Japan); and the Buddhism indigenous to the Tibetan region isVajrayana. That said, the Buddhist temples you will see in China are predominantly Chinese Hinayana with some Theravada temples found mostly in Tibet and western Yunan and Sichuan.

What are some examples of the three types of Chinese temples (Taoist, Buddhist, and folk religion) within Suzhou? Some great examples of Chinese temples can be experienced in one day starting in Leqiao, the center of Suzhou’s old city. In the very center of Leqiao, the enigmatically named Temple of Mystery (Xuanmiaoguan) is an impressive Taoist temple. West of Leqiao, on the north side of Jingde Road is the Chenghuang Miao temple, Suzhou’s City god temple. South of Leqiao, on Chuanxin Street, is the Baoguo Si Temple, a Chan Buddhist temple, which offers a unique glimpse into China’s contribution to the flavor of Buddhism. Going beyond the three most common examples of temple types, south of Leqiao, on Renmin Road, Suzhou even offers a Confucian temple, a large red temple honoring China’s greatest teacher. Differentiating itself from the three previous temple-types, it is slightly more restrained in its iconography. It’s surrounding garden is calm and peaceful, a welcome escape from the overwhelm one may experience when encountering the complexity of China’s temples.