Dave Alber’s article “Ancestors and Immortals: a Foreigner’s Introduction to Ching Ming Festival” appeared in Suzhou, China’s Open Magazine, Issue 138, April 2018.

Dave Alber’s article “Ancestors and Immortals: a Foreigner’s Introduction to Ching Ming Festival” appeared in Suzhou, China’s Open Magazine, Issue 138, April 2018.

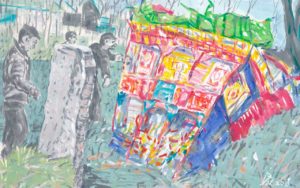

Ancestors and Immortals contains the following travel illustrations by Travel Writer Dave Alber:

• Burning Joss Paper During Ching Ming Festival

• Paper Mansion For Ancestors During Ching Ming Festival

• Lady He of the Eight Immortals

A PDF file of the published travel writing article is here: “Ancestors and Immortals: a Foreigner’s Introduction to Ching Ming Festival” in Open Magazine, Issue 138, April 2018.

The travel writing article is reproduced here:

Ancestors and Immortals: a Foreigner’s Introduction to Ching Ming Festival

by Dave Alber He Wen Ping is marvelous. His house is decorated wall to wall with pages from the Song Dynasty Three Character Classic for his toddling son to practice his Chinese. Thus, his son practices at an early age such Confucian sayings as:

He Wen Ping is marvelous. His house is decorated wall to wall with pages from the Song Dynasty Three Character Classic for his toddling son to practice his Chinese. Thus, his son practices at an early age such Confucian sayings as:

高曾祖,父而身。

身而子,子而孫。

自子孫,至玄曾。

乃九族,人之倫。

In English:

Great great grandfather, great grandfather, grandfather,

father and self,

self and son,

son and grandson,

from son and grandson

on to great grandson and great great grandson.

These are the nine patrilineal relationships,

constituting the kinships of man.[i]

Wen Ping asked some of his English friends to participate in his family’s traditional Ching Ming celebrations. My friend Bill and I were fortunate enough to be able to accept. So bright and early April 4th, Wen Ping and family picked us up in a rented SUV. We drove out of the Henan city of Jiaozuo to a nearby small town where Wen Ping’s family gravesite is located.

People all across China would be visiting ancestral graves this day because Ching Ming Festival is a Chinese holiday honoring family ancestors. The holiday falls on the 1st day of the 5th solar term of the Asian lunisolar calendar. In English it is known as Tomb Sweeping Day. On this national holiday people clean and repair ancestral gravesites and make offerings of food, wine, paper clothing, and fake money.

Wen Ping’s rented SUV parked at the end of a country road alongside other vehicles. We greeted Wen Ping’s brothers and sisters and their families and walked single file on an elevated path between damp clay fields filled with green wheatgrass swaying in the wind.

The gravesite consisted of several unobtrusive unmarked mounds in the middle of the wheat field. Almost immediately the ceremony began. There wasn’t any leader. People had done this their whole lives, so everyone knew what to do. Food was placed on the mounds and colored joss paper, clothes, and money were burned at each mound. The offerings were made in a sequence according to family rank; eldest to youngest, male to female. The ritual was simple and elegant. Wen Ping explained as Bill and I observed the process and kneeled and bowed at the appropriate times. “This is my father. This is my mother and this one here is my grandfather.”

As this was all consistent with what I had read about the festival, I assumed that the holiday was more or less over. However, I couldn’t have been more wrong. For the holiday, the ceremonies, and the fuller extent of ancestor devotion was to unpack more richness, color and surprises than I had anticipated.

We went back to the small town and piled out of the SUV. Wen Ping went into a house and met with extended family. Bill and I walked down the street to listen to some musicians who had set up loudspeakers along the thin dusty alley. It seemed like KTV (Chinese Karaoke) village style. We played the role of foreign celebrities and chatted and posed with the locals as their friends took cell phone pictures. Wen Ping came for us, and to my surprise, the whole assembly, musicians and all, marched in a long parade to another field. This one had many gravestones and piles of huge paper mansions, cars, televisions, and luxury goods. Long strings of firecrackers were draped on the trees. The musicians played the erhu (a stringed instrument); stick percussion; and cymbals, all improvised around a gourd-like wind instrument that sounded something like a high-pitched bagpipe.

Pointing at the graves, Wen Ping explained, “These are our village ancestors. That one over there is the oldest.”

Everyone in this village was more or less related. This truly was a village in the most traditional sense of the word. The village was essentially a clan. We were all at the gravesite to honor shared clan ancestors. Huge piles of joss paper and money were burned. I pitched in to help with the fires. Surprising flash bonfires of paper mansions ignited and then disappeared in seconds. Firecrackers exploded around us. The honking clamor of festival music was an elevated drone holding the event firmly in ritual space.

Everyone in this village was more or less related. This truly was a village in the most traditional sense of the word. The village was essentially a clan. We were all at the gravesite to honor shared clan ancestors. Huge piles of joss paper and money were burned. I pitched in to help with the fires. Surprising flash bonfires of paper mansions ignited and then disappeared in seconds. Firecrackers exploded around us. The honking clamor of festival music was an elevated drone holding the event firmly in ritual space.

Fires burned all around us. And what really is fire? A thing? In Asia, and many traditional cultures around the world, fire is a medium between worlds. It is a process that links the world of objective daylight reality with the subtle and invisible worlds of the dead. And what are the worlds of the dead? Way stations; transitional depots; ethereal realms; natural processes of ecology; archetypical Chinese bureaucracies; places where the deceased learn to shed desires for the transient objects of the sunlit world; locations where the deceased have their personalities mirrored back to them; and heavens and hells in accordance with their karmic merit.

And the burning of joss paper is sending gratitude for the ancestors, the “dead”, who indeed are not dead, as their ambitions, desires, unfulfilled longings, health conditions, ailments, emotional temperaments, and physical traits express, here and now, in everyone in the clan. The more recent the dead, the stronger a living person feels the grasping clutch of the deceased’s emotional attachments in their own life. The more distant the dead, the closer they are to spiritual fulfillment in the abiding reality beyond all transient forms. Indeed, the more distant the dead, the more they resemble the enlightened gods or the abiding serenity of nature.

On this contemplative day, my friend and I had been invited to two family fields. Of what age? How old is this family, the He clan? And how long have they been living on this same land? They had lived here before the Revolution, when this family land became state-owned land. And they had courageously remained here through the Red Guard atrocities, when people, I am told, tore out the largest trees of the gravesites, doing their best to destroy everything traditional. It is quite easy to kill a tree, but an act of supreme strength to maintain a familial continuity for centuries. Bravo!

This large and courageous clan piled into cars and SUVs and headed out to the best restaurant in town. And in a large room absolutely filled with people of every age, we ate, we toasted, we drank, and were fulfilled.

I thought that this was the end of the ceremonies. What more could there be?

We piled back into the SUV and headed to a town temple Wen Ping had pointed out on the way to the restaurant. It had an elevated statue in front of its huge outer wall. “Who is that?” I asked.

“He Tang,” Wen Ping answered. “He is a great ancestor.”

Apparently this was a temple dedicated in He Tang’s honor. And as the SUV drove behind the outer wall, what a temple! A traditional opera stage bolstered the inside of the outer wall and faced a small open-air auditorium. Behind this was an inner temple, a stone bridge over a moat, a small pavilion, steles, and a large temple.

Standing next to a stele that commemorated He Tang’s achievements, Wen Ping explained, “He Tang was born in the Ming Dynasty. He served as the teacher for a Qing Dynasty emperor.”

“Your ancestor?”

“Yes.”

The ground floor of the temple housed a huge statue and altar to He Tang. An illustrated calligraphic scroll along the left wall related the story of He Tang’s life. I was briefly reminded of visiting the Cathedral of St. Francis in Assisi and seeing Giotto’s frescos of the life of St. Francis. Here too was a life story worthy of being told and retold by inspired generations.

The upper story of the temple was locked, but a caretaker opened it for Wen Ping and his family. The walls of the upper story are absolutely covered with illustrated calligraphic scrolls. Each one depicts an episode in the life of He Tang. The first one shows He Tang changing the temperament of belligerent students through the wisdom of his teachings. In the second scroll he is seen educating a young prince. The text reminds educators to be compassionate yet firm. The third scroll shows He Tang instructing men working on a timber roof beam. And so on around the walls in paintings and text that could easily fill a book.

At one end of the room is an altar to the female Taoist Immortal, He Xian Gu. Wen Ping casually mentions, “Oh, yeah. She is part of our family.”

“You have one of the Taoist Immortals in your family?” I asked.

“Yeah.”

I was speechless and utterly stupefied.

The folklore tradition of the Taoist immortals in China is similar to the European tradition of saint stories. They are both hagiographies (spiritual biographies) and tales of local villagers encountering these miraculous human exemplars. Lady He was born over a thousand years ago, during the Tang Dynasty. Villagers were astounded by the six long golden hairs growing from the crown of her infant head. As a child, Lady He was taught the Taoist arts in vivid nighttime dreams. And during the day she practiced the medicinal, alchemical, and longevity practices she learned in dream transmissions from spiritual elders. Legends tell of her yogic accomplishments and spiritual powers. China’s singular empress, Wu Zetian, sought to learn the techniques of immortality from her, but Lady He would always vanish like the reflection of the moon seemingly captured in a cup of water.

The folklore tradition of the Taoist immortals in China is similar to the European tradition of saint stories. They are both hagiographies (spiritual biographies) and tales of local villagers encountering these miraculous human exemplars. Lady He was born over a thousand years ago, during the Tang Dynasty. Villagers were astounded by the six long golden hairs growing from the crown of her infant head. As a child, Lady He was taught the Taoist arts in vivid nighttime dreams. And during the day she practiced the medicinal, alchemical, and longevity practices she learned in dream transmissions from spiritual elders. Legends tell of her yogic accomplishments and spiritual powers. China’s singular empress, Wu Zetian, sought to learn the techniques of immortality from her, but Lady He would always vanish like the reflection of the moon seemingly captured in a cup of water.

Afterward we visited Wen Ping’s birth house and met his cousins and their families who lived nearby. One cousin’s job was to build roof beams exactly like we had seen in the scroll paintings of He Tang. Bill remarked to Wen Ping, “You are a teacher, just like He Tang. Your cousin builds roof beams. I see the continuity of your family traditions.”

The houses in this section of the village were very old. Mortared bricks were used for structural walls, unmortared bricks for much else, providing versatility to landscaping as well as raw materials for future need. I was amazed by the elegance of the tiled roofs. The house that Wen Ping was born in is now abandoned. A house nearby was built by his father, which again, it had the same timber roof beam as depicted in the scroll of He Tang.

Our rapidly modernizing age is characterized by a global loss of traditional culture. People of every nation struggle to compete in a global economy that has a shared materialistic worldview characterized by resource management. As elsewhere, many of China’s traditions are disappearing.

And yet the hands of the living clasp those of their forefathers and on and on and on through time. What gratitude and love must extend through these strong arms back in time, an accomplishment truly befitting the family of the miraculous Lady He. This family, like others all across China, escaped the grasping demands of impersonal authority, like Empress Wu’s clutching after immortality. If not immortality itself, ancestor devotion is at least a form of continuity as deep as cellular biology and as ancient as the earliest burial traditions that love sustains to this very day.

[i]The san tzu ching: or three character classic, and the ch’ien tsu wen, or thousand character essay. By Chou Hsing-Ssu. Metrically Translated by Herbert A. Giles. Shanghai: A. H. de Carvalho, 1873. I have replaced the word “agnates” with “patrilineal relationships.”